The Farm at Black Mountain College

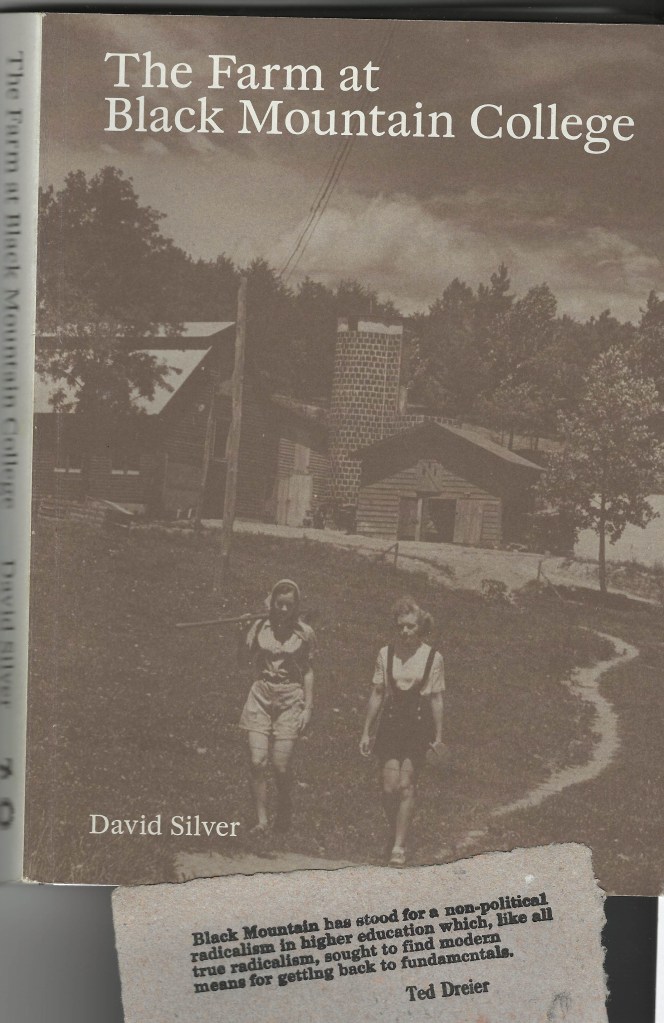

The Farm at Black Mountain College is a new book and the current exhibit (extended through March 15, 2025) at the Black Mountain College Museum + Art Center. Both were to be featured at the annual BMC Conference, cancelled by Helene, and the bookmark in the image above was to be my giveaway at that event. I have watched and learned from David Silver for the last ten years as he has researched and built this project. It has been a joy. David is a professor and chair of environmental studies at the University of San Francisco and has presented at the BMC conference each year about his work. The book and exhibit, closely tied, offer a comprehensive but alternative history of this iconic college, using the Farm as a lens to examine the nuts and bolts of BMC operations, the non-famous students and staff and their massive contributions, and how a sense of community and collaboration permeated the contentious but dedicated efforts to create a unique educational environment, succeeding in that to a level that reverberates in history.

Luck, money and student leadership and involvement all played roles in the genesis of BMC. Casual fans should be reminded that there were two BMC campuses, equally important. The Farm emerged very early in the college’s existence, and major work was done near the Blue Ridge Assembly site. Rooted partly in Dewey’s ideals of education and democracy, founder John Rice, and stalwart board member and fundraiser Ted Dreier saw manual labor as “a gateway to participation in a democratic society, with cooperation and community as vital by-products.” The faculty was expected to provide some farm work (with more or less grudging), but students took on the bulk and showed growing skills and perseverance. Norm Weston, an indifferent student, took on what became a staff position managing farm affairs, and without waiting for permission, obtained the Farm’s first chickens. Nat French, an inaugural student, salvaged dead chestnut trees to help build a pigpen, having already contributed the chicken coop, storage sheds, and coldframes for plant propagation. On the other hand Josef Albers himself. who hailed from a farm community in Westphalia, got involved with that pigpen and regularly came to work sessions.

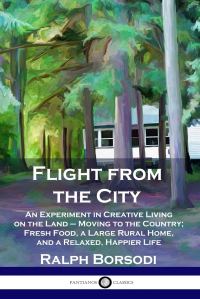

The Farm at BMC got a big head start from the book pictured above. Two weeks into the school’s existence, this book was shared with students by a faculty member and inspired many dreams and discussions relative to the Farm. Ted Dreier read it and expounded on it; Dave Bailey’s chicken coop was directly modeled on the one in the book, and during debates on whether to pursue the Farm, students were “waving a bible in the shape of Ralph Borsodi’s Flight from the City.” The paperback version belonging to the BMC museum is wrapped and on wall display in the show, so I purchased a reprint (as pictured above) to put in the library display next to David’s new book. Not just a how-to, I found surprising ideas within that addressed the way our food system has veered away from direct economic value toward transportation and advertising costs that dwarf the original value of the food.

The farm activities shifted to the new Lake Eden campus before the college itself did. Here, the Work Program begun for the Farm expanded to help create the architectural icon that is the Studies Building. Just up the hill, the barn and silos that were built by students create a magical present-day scene that has been the backdrop for many talks by David Silver at the BMC conference. One of his favorite themes is the relationship between BMC and the conservative mountain community around it. From his book: “It’s inaccurate to claim that BMC did not interact with the surrounding communities,” and the development of the Farm provided many of those interactions. These ranged from training at the nearby Swannanoa Test Farm, a research facility operated by the State of NC, to numerous friendly and extremely helpful visits to and equipment loans from The Farm School, which was founded by Presbyterian women to educate poor rural boys, and went on to become Warren Wilson College. Several local farmers served at various times as farm managers for the college, and provided a local perspective. From selling excess produce in Asheville markets to carrying sows to B.C. Brown and his boars to be impregnated, farm activities generated interaction with the community.

With the Farm as frame, Silver is able to describe other important aspects of BMC history that are not often addressed in studies of the famous artists that helped create its reputation. Jack and Rubye Lipsey operated the kitchen that fed the campus and both became important figures in BMC daily life. They represented the beginning of integration efforts that led to the admission of black students and the hiring of black staff and faculty. Woman were always an important part of BMC life, but during WWII most of the male students were gone, and Silver describes “When The College Was Female,” with Ati Gropius and Elsa Kahl taking charge of the growing dairy operation and Nancy West and Zoya Sandomirksy providing the student labor for construction of the silos. During this phase Molly Gregory, David Silver’s designated “BMC Farm MVP”, dominated affairs with her indefatigable efforts at building farm structures and and developing hands-on experiences for BMC students. Molly managed the Farm so well that by 1943 it produced most of the produce the community ate, plus enough to can hundreds of gallons for winter use.

For all his egalitarian approach, Silver does not leave out the more famous students who were integral to the agrarian accomplishments at BMC. Ruth Asawa traveled to Mexico while a student at BMC and learned to weave wire, which first led to wire egg baskets for Farm use, and then the wire sculptures for which she is world famous. Ruth came from a farming family, thrived at BMC and became expert at producing butter and buttermilk, driving the Farm’s double-clutch four-wheel-drive truck, and raising a roof for the new farm house. Her friend (and my own BMC favorite) Ray Johnson was also very active on the Farm. M.C. Richards, poet-turned-potter who developed the ceramics program, hosted students and treated them to a mean fresh blackberry pie.

This book ends with a detailed description of the physical and financial decline of the college after the departure of John Rice and especially that of Ted Dreier, whose contributions and financial connections were so crucial throughout his time there. The physical decline of the campus is paired in Silver’s description with despair, infighting, and parasitism, with students coming to attend with no intention of paying, the ransacking of the library, and the general decay of buildings and landscape. The book and one caption in the exhibit take a hilariously wicked jab at Charles Olson, the last college rector, who despised the Work Program, disdained his correspondence duties, and generally was a marvelous teacher of writing but a very poor rector. A sad and perhaps inevitable collapse led the college to close officially in 1957. The Farm was an essential component of its many successes, and David Silver documents the many very positive memories it brought to staff and students. As David Weinrib put it, “Instead of gym, we took Farm.”

The Farm at BMC – Atelier Press

No comments yet.

Leave a comment