The BMCM+AC Fires All Cylinders for Ray J’s Paper Snake Show

Something Else Entirely

Ray Johnson, Dick Higgins + the making of The Paper Snake

The summer 2015 show at the Black Mountain College Museum in Asheville presented newly re-discovered archives of publication material for Ray Johnson’s The Paper Snake, designed and published by Ray’s good friend Dick Higgins in 1965 as the second title from Higgins’ Something Else Press. Curator Michael Von Uchtrup found the production material in a large brown paper envelope among the many items in William S. Wilson’s Ray Johnson archive. The envelope lay unopened for 50 years. The exhibit displays original collages, design proofs, an autographed copy of the very rare first printing, and various related material, including hilarious “promotion flyers” produced by Ray for the book. The show came on the heels of the reprinting of The Paper Snake by Siglio Press in 2014.

“The show is full of mysteries,” stated Von Uchtrup at the opening reception on June 5, 2015. The Paper Snake is nearly as much about Dick Higgins’ “translation” of Ray Johnson’s ideas as it is a record of one stream of Ray’s voluminous sendings. Higgins selected and sometimes altered the material, often to Ray’s dismay. Many of the proof pages and original art for the book showed significant differences from the final book, and a few bits of the text seemed to be written by Higgins. Still, the book and the show are filled with lists, tiny plays, letters, quotes from reading, and all the other unique fusions of art, communication and humor found in Ray Johnson’s work.

This was a show to read more than to view. Though greatly enhanced by several early collages on loan from Bill Wilson, the bulk of the show was devoted to images directly related to The Paper Snake. Large proofs sequenced on the wall enabled one to actually stand and read the book in proof form.The display tables held much dense typescript that usually rewarded closer inspection. A special treat was the audio-visuals: three audio-cassette records of performance works by Ray Johnson, a Dick Higgins poem recitation, and 1965 8mm films of Ray. Even the book selection on the sales shelf offered a wide and valuable range of titles relevant to the show, including of course, the book itself. The reprint was issued in the same print run as the original, 1840 copies. Siglio Press calls it a “vertiginous,mind-bending artist’s book … far ahead of its time.”

The events surrounding the show not only illuminated the book but also presented a fine example of the wonderful work done by the BMCMAC staff and its presenters in providing context and local artistic collaboration to deepen our connection to Black Mountain College. The day after the reception, the curator was joined by Julie J. Thomson for a freely flowing discussion based on slide images of the career and artistic significance of Ray Johnson. Julie has set herself the task of discovering “how one becomes an artist like Ray Johnson,” and her close reading of resonances within the book and her honest embrace of the ambiguity and occasional frustration of dissecting Ray’s inscrutable processes made for a fascinating sharing. Michael Von Uchtrup is working on a biography of Ray, and he emphasized many learnable moments derived from close attention to the materials in his discovery. Julie and Michael’s reminiscences of interviews and anecdotes echoed a strong theme in the documentary film about Ray: no one really knew Ray Johnson, or everyone knew a different side of him. Julie and Michael’s perspectives on the show were offered in full length essays in the large brochure accompanying the show.

On July 3rd, a full audience enjoyed the presentation of “In the Arm of Flowers”, a performance by Megan Ransmeier and Julia Rich. The themes of correspondence, communication over space, and isolation played out in dance movements, readings and evocative vocalizations by the two artists. Their performance was based on three years of correspondence, and was dedicated to Ray’s work. In the exhibit’s final public event Alice Sebrell gave a strong introduction to the screening of “How to Draw a Bunny“, the award-winning 2002 documentary featuring 1995 interviews with Christo, Chuck Close, Roy Lichtenstein and others.

This array of features was capped by the publication of Volume 8 of Black Mountain College Studies, which was dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the publication of The Paper Snake as well as the exhibit under discussion. It includes essays, interviews, and many topics for further exploration. With Sebastian Matthew’s 2010 show on Ray’s early years, the BMCMAC has provided a Ray J fan (and past correspondent) like myself with a rich set of experiences and learning opportunities. This exhibit provided the general and artistic community with another window into the unique and ground-breaking work that emerged from BMC. It took some fairly esoteric and technical materials and turned them into a show and event schedule that provided for a very enriching summer at the BMCMAC.

Book Arts, Farming Fueled Black Mountain College

The 2013 Black Mountain College conference, held at UNC-Asheville, covered much ground, as always, with reflections and insights regarding the methods, influence and legacy of the experimental college that is both revered and obscured in the history of 20th century education and art. I always come away with one or more real breakthroughs in my thoughts about these topics, and this year the BMC farm program really came to light in the presentation of David Silver. Tom Murphy spoke of the print shop and letterpress operations, and both of these sessions offered rich, practical examinations of the processes and their implications. As always, the foundation of factual knowledge and interpretation laid down by Mary Emma Harris in her 1987 book, The Arts of Black Mountain College, is acknowledged and utilized by all presenters. Ms Harris continues to lead BMC research efforts, and presented this year about BMC approaches to material studies. She showed how the low-budget humble materials used by Anni Albers and others provided a freedom and at the same time an enforced discipline on the students. “You mustn’t forbid the possibilities of the materials,” and in the notes of Ruth Asawa from Josef Alber’s class, “the whole cosmos is entertaining”. These topics were applied to Asawa, BMC sculptural artist, by Jason Andrew, who showed how Ruth Asawa’s zero-based explorations of the culture of handicraft, and her highly artistic use of negative and positive space, helped lift craft into the perceived realm of art in the mid twentieth century. Christopher Benfey, the featured speaker whose ideas I discussed in the previous post, gave a keynote speech which emphasized a similar theme: “Starting at Zero!” Get your hands involved with available material. Then make an honest response to the materials, including the industrial process involved. The conference highlighted the synergy and profound influence derived from the joining of the design philosophy of Albers and the progressive education ideals of John Rice. Experiential education and the approach of design as a “form of justice between man and material” made BMC the birthing place of many new currents in American art.

The BMC farm was a rich source of experiential education, surely, and its operations offered many practical lessons in form and design. David Silver of the University of San Francisco described how students, with Ted Dreier’s supportive oversight, had a huge influence on the development of the farm. From Harris’s book: “In the first year [1934] a vegetable garden was started by Norman Weston [BMC student and “treasurer”] and other interested community members. The college leased a 25 acre farm with a vineyard and apple orchard…” John Rice was not enthusiastic but didn’t mind as long as faculty obligations were not needed. In 1938 the farm went to the future Lake Eden, was expanded in 1941 and by 1944 “was producing most of the beef, pork, potatoes, eggs, dairy products and some vegetables used by the college” (Harris again). Last year and this, Silver offered rich detail into how the farm emblemized the integrated systems, the balance of discipline and freedom, and the “use what you find” attitude that characterized much of the college’s history. His research anecdotes, from local farmers such as Bass Allen, who taught the students how to farm, to the very Albers-like egg lists that recorded every oval, both entertain and enlighten. Mistakes, both horrible and hilarious, were made. But students gained invaluable experiences, including the closest thing BMC offered in the way of physical education. Molly Gregory, who taught woodworking and maintained the mechanical shop, took over the farm in the later years of the college and operated it at a profit. Silver’s admiring portrayal of her BMC work showed that, like Asawa, she helped create an atmosphere that bridged the gap between artisan and artist, that found a space for sublime work of the hands.

Of particular interest to me was my own arena of artisanry; the letterpress printing and other book arts that were pursued at BMC. Tom Murphy from Texas A&M Corpus Christi recounted printing efforts that were of practical help to the college but eventually played a role in the establishment of literary forces and the Black Mountain Poets as important threads in the history of BMC. Again with the support of Harris’s history, he described how Xanti Schawinsky, a noted graphic designer, helped obtain type and a press for a print shop in Lee Hall on the first Blue Ridge campus. The bulletins printed were “not flashy’ and in fact were conventional products that advertised the best face of the college to outsiders. Students like Ed Dorn and John McCandless received hands-on learning and were able to design and effect their own projects. The print shop had a long hiatus before and during the war, but in 1946 was resurrected as part of the wood shop and used in writing projects involving Jimmy Tite, Harry Weitzer, and Ann Mayer. A visit by Anais Nin in 1947 was the catalyst for new literary publications, including Poems by M.C. Richards in 1948. This set the scene for the Olson years, when BMC nurtured energies that traveled to the west coast, Paris, and North Carolina’s own Jargon Press, published by Jonathan Williams. (A fun footnote to the latter is that the BMCM+AC has acquired the imprint and publications of the Jargon Society!)

All of these insights need fuel themselves to become realized. The first session of the conference highlighted the newly emerging resources for such work. UNC-A’s Ramsey Library is digitizing and organizing web pages for several BMC collections. The Western Regional Archive continues to add collections,including the BMC Project papers, generated and collected by Mary Emma Harris. The state archive has selected BMC documents in their online archive. The Black Mountain Studies Journal offers ongoing scholarship in the field. Rich resources indeed!

Design is not decoration, design means an understandable order. It is understandibility. It is not beauty. If it is understandable, it is beautiful. Josef Albers

Book arts came up in one last surprising setting – Julie Thomson‘s highly stimulating talk on Ray Johnson’s commercial design work. She offered the quote above and astounded the audience with images of standard New Direction titles whose covers were designed by Johnson and one of his mentors, Alan Lustig. She pointed out that Ray J had done prize-winning poster work back in Detroit, was a perfectly competent graphic designer – and helped promote the idea of integrating typography with visual art and design.

Congrats to the BMCM+AC for another great conference!

BOO KOF KNO WLE DGE – Ray J’s Zen Icons

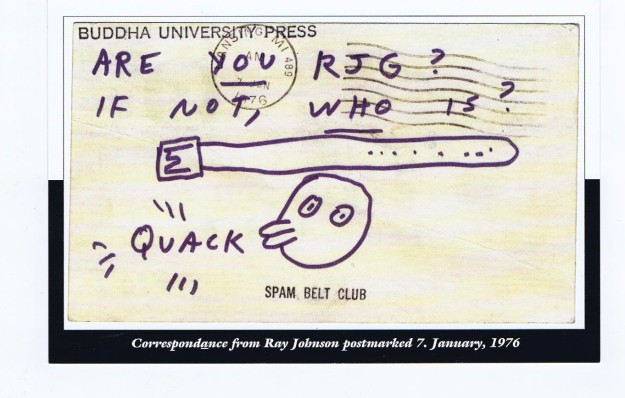

The BMC conference in October 2010 at UNC-A offered a wide range of wonderful BMC nuggets, but having put off posting about it so long, I’m sticking with the Ray Johnson material which is always my main priority. A big highlight was John Held’s mail art show and talk about mail art and the early days of the NY Correspondance School.

Ray’s inscrutable, radical but disarming approach to art has clearly led to a rich but fairly specialized body of critical writing and thinking about his work, immeshed but not entangled in the large “fan” following evident online. The main points of the former relate to Black Mountain College influences, the main thrust of the latter is mail art and performance art. Ray did not appear to observe such distinctions, but one thing I gained in the last two years of learning from BMCM+AC venues for Ray J work is that Ray Johnson was a major artist in the tradition of DuChamp, Miro, and Klee. Slowly, a body of academic work is relating his truly astonishing accomplishments both in the mainstream tradition of painting and his unique and irresistible gift and mandate: “Steal beauty from the mundane.”

The conference presentations offered delicious details about Ray’s process. Sebastian Matthews provided the quote above as he compared Ray’s obsession with found images to the “image collage” of Frank O’Hara poem “A Step away From Them.” Sebastian also elucidated with great insight about Ray’s Moticos, the secret embeddings and abrupt juxtapositions that Ray created in response to his environment. For Sebastian, Ray is a zen master of art, always indirect though immediate, balancing inward and outward by being aware of the act of being aware. Like O’Hara, a New York School poet, Ray scoured the city for images that enabled him to subvert and reconnect meanings.

Louly Peacock described how Ray subverted Pop Art (and pre-dated Warhol with celebrity portraits), teasing the major figures as in labeling Pollock “Action Jackson,” a nomiker that stuck. Her survey of phallic imagery in Ray’s work made her yet again the most entertaining speaker at the conference. Julie Thomson helped frame Ray’s performance art in showing the relationship between Ray and George Brecht of Fluxus fame, who” began to imagine a more modest, slyly provocative kind of art that would focus attention on the perceptual and cognitive experience of the viewer.” Brecht created “instructions for a toward event,” and along with Alan Kaprow paved the way for the Happenings – not to speak of Ray’s Nothings. Johanna Gosse portrayed Ray as a renegade of the gallery art world, deliberately obfuscating the market process, living in the “osmotic fluid flow” of daily aesthetic experiences, where the experience is the end, the process is the product.

Kate Dempsey revealed more of her discoveries about Albers’ fascination with pre-Columbian culture and how the Mayan hieroglyphs – still mysteries at the time- helped develop Ray’s sensitivity to text as an image source. Ray retained a geometric precision even as he evolved out of painting, and his love of codes, puns and multiple meanings ties together his early and late work.

The best insights into Ray were to be found at the talk by John Held while sorrounded by his mail art show. He walks the walk with mail art to this day and had much to share. He confirmed something also mentioned in the panel discussions – Ray’s moticos were featured in the very first Village Voice in 1955. He also described the importance of the 1970 correspondence art exhibit at The Whitney. He made it convincingly clear that Ray’s correspondence art was “not about the postal system,” but about “how you communicate aesthetics over a long distance.” Held stated that “Ray was building a community,’ and used no judgment or selection with his mailing lists.

The mail art show he exhibited had 170 entries from over 40 countries. It was impressive, entertaining, and a great tribute to the ongoing spirit of the NY Correspondance School. Ray Johnson continues to generate not only interest and academic attention, but exciting participatory tributes and art directly tracable to his genius.

*******************************

One fun event I should share about from last fall is the presentation of a new BMC Wall in downtown Asheville. A large mural and several interesting installations grace an alley just off Broadway.

Several of the writers mentioned above are featured with Ray Johnson articles in an upcoming issue of the

Journal of Black Mountain College Studies

Sebastian Matthew’s Ray J show essay with lots of Ray J images!

Raleigh Rambles Black Mountain page

Raleigh Rambles Ray Johnson page

Ray Johnson Show a Multiple Power Play

“to make open the eyes” Josef Albers All work of Ray Johnson on this site is used by permission of The Ray Johnson Estate

All work of Ray Johnson on this site is used by permission of The Ray Johnson Estate

BMC to NYC: The Tutelary Years of Ray Johnson (1943-1967)

Ray Johnson was probably the most enigmatic and least appreciated artist of his importance in the 20th century. He was a man of many many layers, not so much depth, on first impression, just layers, fairly random factors that underlie and overlay his work. The show just ended at The Black Mountain College Museum and Art Center had many layers itself, over multiple valuable events, and provided a greatly needed showcase and explication for this “seminal figure of Pop Art” whose collages “influenced a generation of contemporary artists.”

The show and especially its catalogue were already reviewed here, but several subsequent events have enriched the impact of the show. Dr. Francis F. L. Beatty (quoted and seen above), a curator who works with the Ray Johnson Estate, gave a lecture at the BMCM+AC on May 21, using parallel slides to show that Ray displays elements in his collages that link him to the major artistic trends of the day. His wit, humor and intense communications of all kinds were highly stimulating but hard to classify, but his collages and the palette he created out of found and encountered material can be seen as fully in the tradition of Klee’ as well as Albers, while partaking of the humor of Dada. “I don’t make pop art. I make chop art.” Ray’s statement refers to his use of old work in new, and Dr. Beatty skillfully elucidated the way in which Ray’s “chop art” (often meticulous geometric constructions) came right out of his Black Mountain experience. She makes a point that reverberated through this show: the liberation of American education happening at Black Mountain served as well to “liberate Ray Johnson.” He found himself, and he found the principle that best illuminates the breadth of his work for me: images standing in for words, words become imagery.

Yet Ray remains enigmatic. Dr. Beatty spent much time on the 55 Moticos – huge intricate collages – which Ray made and destroyed, calling them “some of the earliest and most significant examples of Pop Art.” She recounted many personal interactions with Ray, such as the time he approached her and finally wanted to do a gallery display – of “Nothings.” Beyond his inscrutability, his avoidance of the commercial process, Dr. Beatty makes a simple but important point – the small scale of Ray’s visual work limited his gallery prospects and indirectly his artistic stature.

The scale of Ray’s imagination and willingness to live his life for art was unbounded, of course. The final night of the show, orchestrated by curator Sebastian Matthews, was a truly wild and wonderful event that did much to reflect Ray’s spirit. Music, poetry, and spoken word all filled the space.

“We have to seize the things we need to create.” These words were spoken in Picasso’s voice by Keith Flynt, one of the closing night performers (seen below).

Earl Bragg, seen above, offered a nine-eleven poem that featured number names – worthy of Ray’s glyphs and puns. His political themes and passionate phrases made for an excellent reading.

Local dramatists staged a reading of a collaged piece incorporating Ray’s play inside a play about Ray discussing a play with pink James Dean.

The final word has to go to Sebastian Matthews, who did such a magnificent job not only of putting on the show but of staying in touch with Ray’s spirit the whole time. He evoked and nurtured the image of Ray as filled with humor, energy – and a total lack of any sense of propriety. About the “chop art” and “lost art” which was so prominent in the show, he says: “Ray loved to make things up, kill them off, and resurrect them.”

The Ray show is dead, long live the Ray show.

Ray Johnson: Tracking Deep Currents

The Ray Johnson show at the Black Mountain College Museum in Asheville opened February 19th and will run through June 12, 2010. The opening was spectacular, the show is rich, varied and informative. For Ray J fans like me, the catalogue and it’s essays, assembled by show curator Sebastian Matthews, is the real treasure. Sebastian spent over a year studying Ray’s life and work, making connections with important people in Ray’s life (Ray passed in an act of suicide in 1995), and establishing his own perspective on the evolution of Ray’s art from a young art student in Detroit through a strong experience at Black Mountain College to an important role in the art scene of East Village in the 60’s and 70’s. The show displays extensive early work, including fairly typical ink doodles of 14 year old Ray, but also hilarious cards and visual puns from this period that presage his later work.

The show also reveals the aspect of Ray’s work I most needed to learn myself – that Ray came of age as an artist in the painterly traditions BMC and Josef Albers provided, and did lots of wonderful work as he evolved from painting to collage and then on to the correspondence work or “postal performances,” as Isa Bloom calls them, which made him most famous. The show focuses on Ray’s emergence out of Black Mountain College into the New York scene immersed in the ideas of his BMC mentors but prepared to follow Alber’s dictum: “to follow me, follow yourself.” As Sebastian Matthews says in his catalogue essay, “Ray was ripe for the challenges and experiences Manhattan had to offer.” He became one of the most intriguing and complex artists of the 20th century, and this show delineates many of the roots and threads that set him on his path.

The opening of the show was well attended and featured some aspects Ray might have liked very much, though he generally was quite ambivalent about exhibiting or selling or even saving his work. Poetix Vanguard offered spoken word performances during the event, and an open mike followed at a bar nearby. The BMCM+AC library, with many Ray J items prominent, provided a nice context for the highly varied show. Several of Hazel Larsen Archer’s gorgeous photos of Ray at BMC were on display. And Sebastian Matthews, collage artist himself and so clearly a Really Great Guy, presided with enthusiasm over the many energies he had gathered to celebrate the amazing career of Ray Johnson.

The catalogue contains 46 color plates, over a dozen images in the text, and several of Archer’s photographs. It also contains an interactive feature: a pair of postcards bound in as endpapers which the reader is invited to alter as desired and send off: one to a friend and one back to The Black Mountain Museum and Arts Center, whose program director Alice Sebrell is credited by Sebastian as being integral and vital to the process of creating the show. Five essays offer views of Ray that are remarkably varied and complementary.

Sebastian Matthews presents his curatorial essay as nine journal notes written while building the show. He elaborates his basic point: that Ray Johnson “used Black Mountain College as a springboard to propell himself into the Manhattan art world.” He also does a remarkable job, with his intense self-examinations, numerous concrete biographical insights, and constant awareness of Ray’s own probable intent to be inscrutable, of helping us have a “fuller sense of what Ray attempts when he sits down to make art, when he prepares to send out the work to be received, passed on, altered.” The quote is what Sebastian hopes to accomplish with the show, and I think he got there. He also truly transformed my personal sense of Ray J by portraying the intense, painterly, quite technical control Ray exerted over his collage work.

Ray Johnson’s career had many layers, and two essays by old friends of Ray offer insight into his early days in Detroit and his heyday in the East Village. Arthur Secunda contributed much material for the show and portrays in his recollection “Ray Johnson’s intelligence, mysterious youthful verve and artistic ingenuity.” William S. Wilson, the primary lender of the collage works, and one of Ray’s long-time art buddies, makes his essay a tour de force in Ray J style quirkiness and abrupt juxtapositions. He says “Ray Johnson was a student of the imaginations of other people.” He ably describes Ray’s focus not on abstract ideas but direct concrete responses, because Ray “worked to remain within immanences, eluding transcendentals.”

Two academic writers share their ideas about the inportance and significance of Ray’s work. Julie J. Thomson thoroughly documents the large and lasting influence Josef Albers had on Ray’s work. She also describes the way Ray’s work related to the “Happenings” and other art trends of the times. Kate Erin Dempsey, in “Code Word:Ray,” shared a long excerpt from her work in progress about Ray and his reaction to and use of the fad for secret codes and hidden messages raging in the 1950s. Expanding on the fascinating work she shared at the BMC conference, she convincingly demonstrates Ray’s fascination with language and its manipulation for artistic purposes. Furthermore, she follows this thread from radio show decoder rings through the Mayan hieroglyphics and glyphs revered at BMC, to Ray’s mature use of found images – giving them a “new lease on life – enhancing or altering their meaning entirely by arranging them in novel ways.” Kate’s work at the BMC conference, this essay, and hopefully her future book will all warrant future Ray J posts.

The kernel I found that connected all these essay? Nothings – empty shells of meaning – e.g. nonsense – that serve as markers and triggers for the kind of nonlinear art experience Ray Johnson wanted you to have. William S. Wilson talks of “the surface concealed only by another surface.” Julie J. Thomson finds their roots in “the gap, an element emphasized by Albers in his teaching,” and makes the valid and often repeated connection between Ray’s study of Taoism and these ideas. Kate Dempsey makes it clear Ray wanted to avoid specific meanings, sending messages in bottles to be partly constructed by the finder. Sebastian reminds us that Ray was “an autodidact student of Buddhism and a self-described disciple of John Cage’s cultivation of chance occurrence. ” Julie Thomson describes the performances Ray created entitled “Nothings:” they “interrupted the Happenings, opening up a space amidst the busy environments and experiences of the Happenings.” Ray brought Zen and his unique fusion of life and art into American art, and made his mark with great gifts and energy.

Sebastian Matthews has provided an amazing set of Ray Johnson experiences to me , starting with the BMC conference, many kind and enthusiastic interactions, and now this multiple-event, long-running show. He did all the myriad tasks and jumped through all the hoops to make this show happen, but he clearly handled the situation as a working artist and remained beautifully true to the spirit of Ray Johnson with everything he did as a result. See this show and then follow Sebastian’s advice:

Don’t get too caught up in finding meaning in every little detail. You need to first catch a drift of the mood and follow it back in. Let the work show you how to see. Let Ray work his magic. Sebastian Matthews, from BMC to NYC

The event was a blast and was just the beginning. Remember the show runs til June 12th, and there are lots of special events to help motivate the trip. A collage workshop by Krista Franklin had occurred by this post, a screening of How to Draw a Bunny, an award-winning Ray J documentary will take place on April 8, and Dr. Francis F. L. Beatty, a curator who works with the Ray Johnson Estate, will speak about Ray’s work on May 21. The show will celebrate its closing with a poetry reading on June 12th. The Black Mountain College Museum and Art Center, sponsor of all events, has just announced a fascinating weekend event at the old dining hall building on the BMC campus. Sounds fun! BMC lives!!