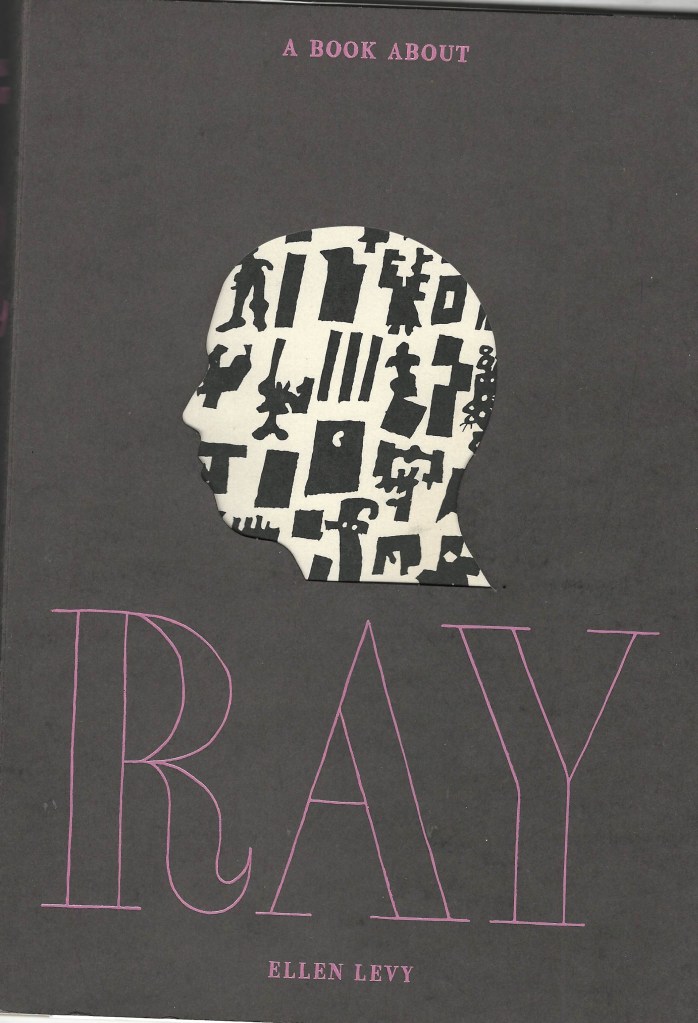

A Book About Ray by Ellen Levy

A Book About Ray by Ellen Levy

Looking with side-curve head curious what comes next

Both in and out of the game and watching and wondering at it.

From “Me Myself”

Walt Whitman

I knew I wanted to be a writer by age 15, but I didn’t come to art as a practice until experiencing the large exhibit of Ray Johnson’s correspondence art in my hometown of Raleigh in 1976. The stunning sense of wonder and delight in the everyday and the radicalization of the locus and purpose of art in this show set me on the life-long journey I have traveled through book arts, performance art, alternative small press publishing and mail art. Yet Ray Johnson and my experience in corresponding with him over the following year were and have remained an enigma to me, even as I have studied his life and career over the last decade due to Sebastian Matthew’s show and other events at the Black Mountain College Museum & Art Center. Ellen Levy’s new book offers the best understanding of Ray and his work I have ever encountered, and her eminently readable and remarkably thorough account is a gift to anyone who is a fan of Ray’s work.

Ray Johnson was born in 1927, just a year after my father, in Detroit Michigan, showed talent early, attended Black Mountain College, moved to New York City with one of his teachers, and became known, eventually quite notoriously, as “New York’s most famous unknown artist,” That irony is a perfect signpost for the absolutely unique, frequently puzzling, and always intriguing art of Ray Johnson, which Ellen Levy shows to be unified in all its many formats as a body of very important work with a strong consistent aesthetic. His life seemed to have been completely devoured by his art, but he lived art so beautifully and honestly that one can always learn something from him and usually get a big laugh or chuckle as well.

Levy gives us not a biography, but the story of his art, which frames his life but excludes what the art doesn’t present for examination. For years I have followed the work of friends who have emphasized the collage work, the way Ray fits into the canon of major art, and the unique pathways he found in correspondence and performance art. (Sebastian Matthews, Kate Dempsey Martineau, and Julie Thomson respectively). Ellen Levy clearly immersed herself with radical depth into the vast and difficult array of Ray Johnson’s work and practices and brings all of the above into a coherent focus. Her approach is described on the dust jacket as “elliptical” and she is certainly remarkably thorough as she sifts through Ray’s archival history, one he planned and organized for just such a researcher as herself. Ray himself comes across through the story as unchanging and un-changable, but she finds the plot in his endlessly various narratives and makes us feel the arc and inevitable denouement of his story, which he ultimately fused with his personal life in a tragic way. But that doomed arc touched on large and important accomplishments and this book admirably argues for their place in the legacy of the New York School of artists and its outgrowths.

I love the ways in which Ray Johnson was famous-adjacent, and I learned from Levy’s book just how obsessed he was with fame and its ecology of connections. The quote about “most famous unknown” is from a New York Times art critic mentioning one of his relatively few gallery shows. The Village Voice, in its very first issue in 1955, ran a story about Ray and his moticos, which was the series that seemed to take him away from painting and into what became correspondence art. Levy documents Ray’s substantial exhibition in a couple of major galleries and many less so, but he strongly resisted exhibition and subverted any attempts to control his process. Subversion became central to his work, especially in regard to fame. Like many, my favorite Ray Johnson collages are the Elvis and James Dean portraits, which are so painterly as not to qualify for Levy as proper “moticos.” By the time period in which I corresponded with Ray, Levy describes him as losing his way a bit, partly due to the overwhelming but not particularly gratifying demands of mass correspondence. Ellen Levy discovered him well after the turn of the century through the semi-viral video “How to Draw a Bunny,” which lovingly and convincingly argues that Ray’s suicide in 1995 was a genuine act of performance art. This book certainly makes one feel Ray might have finally felt that his work had indeed eclipsed his life.

Ray was a performance artist in direct and diffused ways. His contributions to the Happenings movement in postmodern art included announced gallery events as well as improvised NY sidewalk encounters while foraging for collage supplies. His sidewalk display of moticos, with the assistance of friend and art critic Suzi Gablick, could be compared to Joseph Beuys. But whenever Ray Johnson was in public and also in many, if not most, personal situations, he was acting out a persona recognizable to anyone who got to know him. When mystifying or annoying audiences on his college art lecture tour, offering impossible trade terms and conditions to a gallery owner, being interviewed – oh, the interviews! A great companion to Levy’s book is That Was the Answer, edited by Julie Thomson, which chronicles the hilarious, telling and charming way Ray resisted any normal interview. Yet he always seems, well, deadly serious. The empty silhouette of Ray on the cover of A Book About Ray seems a fitting portrait of a person who let his work and artistic beliefs fill out all the corners of his life.

Ray Johnson is difficult, in many ways. Ellen Levy says “I like difficult art.” With his monotone sarcasm and endless detours into esoteric or oblique references added to his grave mistrust of the commercial aspect of fine art, Ray never made it truly big in Fine Art, but his cult-like following and the gradually building body of scholarship and retrospect exhibitions offer anyone willing to make the effort a chance to discover the wonders and delights of this artist. His whimsical use of everyday images, verbal coincidences, and found puns provided a vocabulary he used to describe a popular culture with which he seemed both obsessed and slightly appalled. This book is a fine handbook for your arduous journey.

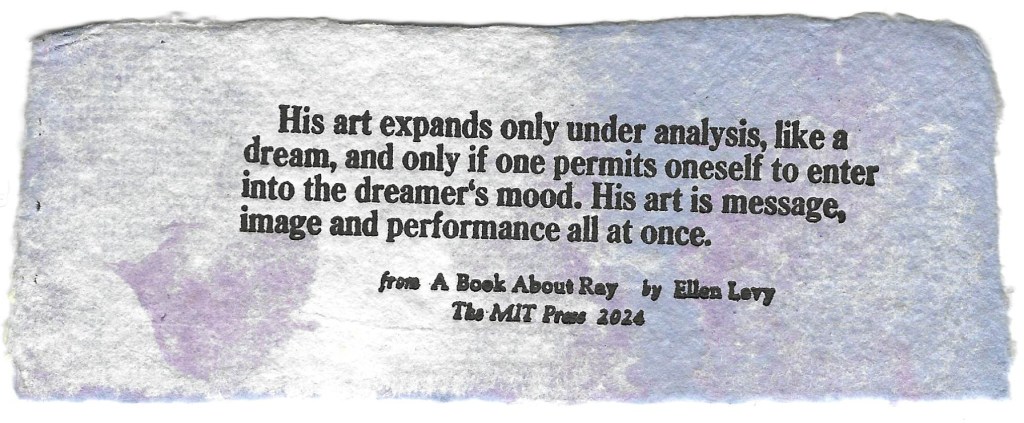

This is the bookmark I will be giving away at the upcoming conference

ReVIEWING Black Mountain College

Co-hosted by BMCM+AC and UNC Asheville

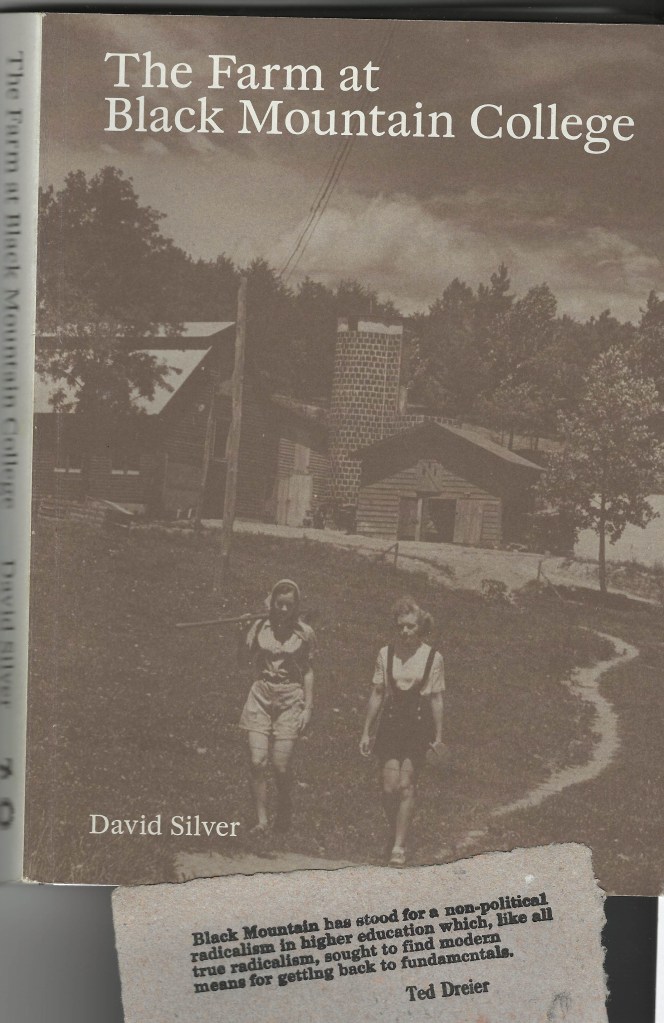

The Farm at Black Mountain College

The Farm at Black Mountain College is a new book and the current exhibit (extended through March 15, 2025) at the Black Mountain College Museum + Art Center. Both were to be featured at the annual BMC Conference, cancelled by Helene, and the bookmark in the image above was to be my giveaway at that event. I have watched and learned from David Silver for the last ten years as he has researched and built this project. It has been a joy. David is a professor and chair of environmental studies at the University of San Francisco and has presented at the BMC conference each year about his work. The book and exhibit, closely tied, offer a comprehensive but alternative history of this iconic college, using the Farm as a lens to examine the nuts and bolts of BMC operations, the non-famous students and staff and their massive contributions, and how a sense of community and collaboration permeated the contentious but dedicated efforts to create a unique educational environment, succeeding in that to a level that reverberates in history.

Luck, money and student leadership and involvement all played roles in the genesis of BMC. Casual fans should be reminded that there were two BMC campuses, equally important. The Farm emerged very early in the college’s existence, and major work was done near the Blue Ridge Assembly site. Rooted partly in Dewey’s ideals of education and democracy, founder John Rice, and stalwart board member and fundraiser Ted Dreier saw manual labor as “a gateway to participation in a democratic society, with cooperation and community as vital by-products.” The faculty was expected to provide some farm work (with more or less grudging), but students took on the bulk and showed growing skills and perseverance. Norm Weston, an indifferent student, took on what became a staff position managing farm affairs, and without waiting for permission, obtained the Farm’s first chickens. Nat French, an inaugural student, salvaged dead chestnut trees to help build a pigpen, having already contributed the chicken coop, storage sheds, and coldframes for plant propagation. On the other hand Josef Albers himself. who hailed from a farm community in Westphalia, got involved with that pigpen and regularly came to work sessions.

The Farm at BMC got a big head start from the book pictured above. Two weeks into the school’s existence, this book was shared with students by a faculty member and inspired many dreams and discussions relative to the Farm. Ted Dreier read it and expounded on it; Dave Bailey’s chicken coop was directly modeled on the one in the book, and during debates on whether to pursue the Farm, students were “waving a bible in the shape of Ralph Borsodi’s Flight from the City.” The paperback version belonging to the BMC museum is wrapped and on wall display in the show, so I purchased a reprint (as pictured above) to put in the library display next to David’s new book. Not just a how-to, I found surprising ideas within that addressed the way our food system has veered away from direct economic value toward transportation and advertising costs that dwarf the original value of the food.

The farm activities shifted to the new Lake Eden campus before the college itself did. Here, the Work Program begun for the Farm expanded to help create the architectural icon that is the Studies Building. Just up the hill, the barn and silos that were built by students create a magical present-day scene that has been the backdrop for many talks by David Silver at the BMC conference. One of his favorite themes is the relationship between BMC and the conservative mountain community around it. From his book: “It’s inaccurate to claim that BMC did not interact with the surrounding communities,” and the development of the Farm provided many of those interactions. These ranged from training at the nearby Swannanoa Test Farm, a research facility operated by the State of NC, to numerous friendly and extremely helpful visits to and equipment loans from The Farm School, which was founded by Presbyterian women to educate poor rural boys, and went on to become Warren Wilson College. Several local farmers served at various times as farm managers for the college, and provided a local perspective. From selling excess produce in Asheville markets to carrying sows to B.C. Brown and his boars to be impregnated, farm activities generated interaction with the community.

With the Farm as frame, Silver is able to describe other important aspects of BMC history that are not often addressed in studies of the famous artists that helped create its reputation. Jack and Rubye Lipsey operated the kitchen that fed the campus and both became important figures in BMC daily life. They represented the beginning of integration efforts that led to the admission of black students and the hiring of black staff and faculty. Woman were always an important part of BMC life, but during WWII most of the male students were gone, and Silver describes “When The College Was Female,” with Ati Gropius and Elsa Kahl taking charge of the growing dairy operation and Nancy West and Zoya Sandomirksy providing the student labor for construction of the silos. During this phase Molly Gregory, David Silver’s designated “BMC Farm MVP”, dominated affairs with her indefatigable efforts at building farm structures and and developing hands-on experiences for BMC students. Molly managed the Farm so well that by 1943 it produced most of the produce the community ate, plus enough to can hundreds of gallons for winter use.

For all his egalitarian approach, Silver does not leave out the more famous students who were integral to the agrarian accomplishments at BMC. Ruth Asawa traveled to Mexico while a student at BMC and learned to weave wire, which first led to wire egg baskets for Farm use, and then the wire sculptures for which she is world famous. Ruth came from a farming family, thrived at BMC and became expert at producing butter and buttermilk, driving the Farm’s double-clutch four-wheel-drive truck, and raising a roof for the new farm house. Her friend (and my own BMC favorite) Ray Johnson was also very active on the Farm. M.C. Richards, poet-turned-potter who developed the ceramics program, hosted students and treated them to a mean fresh blackberry pie.

This book ends with a detailed description of the physical and financial decline of the college after the departure of John Rice and especially that of Ted Dreier, whose contributions and financial connections were so crucial throughout his time there. The physical decline of the campus is paired in Silver’s description with despair, infighting, and parasitism, with students coming to attend with no intention of paying, the ransacking of the library, and the general decay of buildings and landscape. The book and one caption in the exhibit take a hilariously wicked jab at Charles Olson, the last college rector, who despised the Work Program, disdained his correspondence duties, and generally was a marvelous teacher of writing but a very poor rector. A sad and perhaps inevitable collapse led the college to close officially in 1957. The Farm was an essential component of its many successes, and David Silver documents the many very positive memories it brought to staff and students. As David Weinrib put it, “Instead of gym, we took Farm.”

The Farm at BMC – Atelier Press

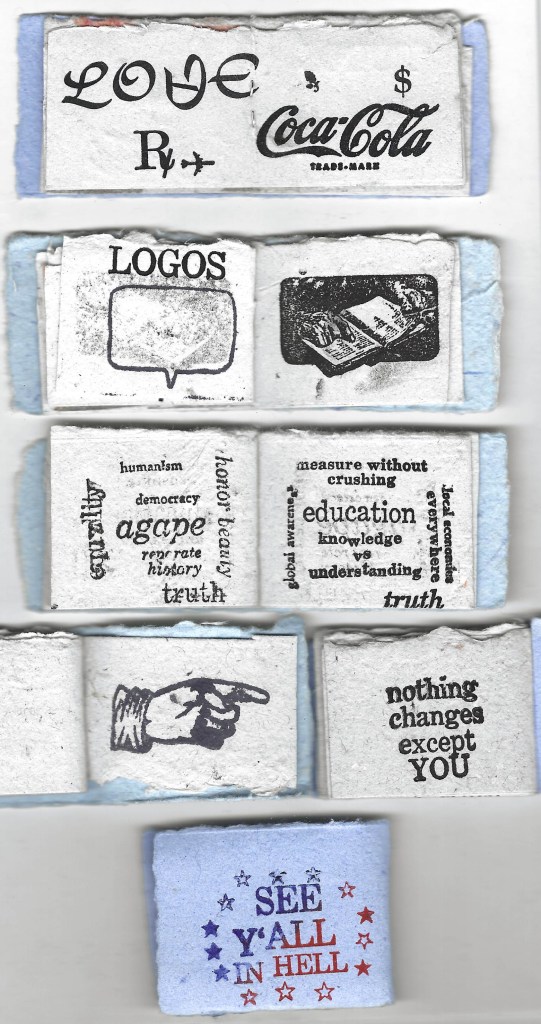

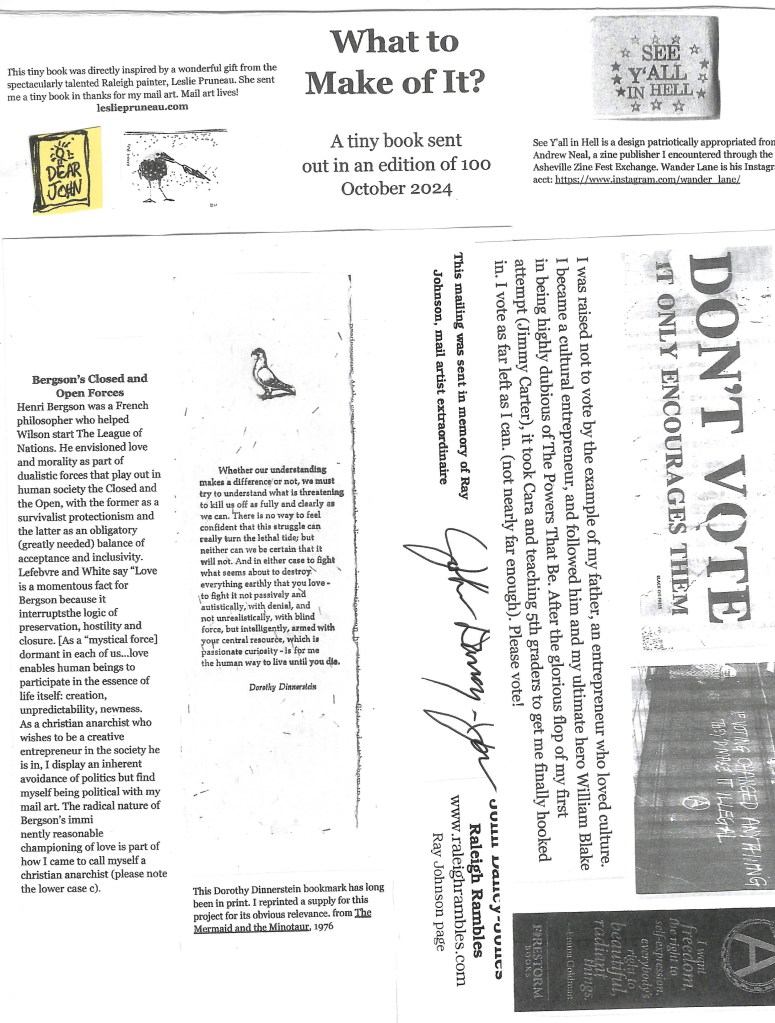

What To Make of It? What will YOU make out of it: mail art

Helene’s fury found me two-thirds through a major mail art project. With the content committed to a pre-election release, I found a way to keep working on it, printing by battery light with a helpful mirror just outside the studio on sunny days. This piece was always going to be “rustic,” even for me, but it was finished in near desperation, taking breaks from printing to shovel silt out of the book arts barn.

The inspiration for this piece came from Leslie Pruneau, a talented and well-established Raleigh artist, who sent me a wonderful tiny book as a gift in return for my mail art. As soon as I saw it, I knew how I wanted to use the hundreds of one inch strips of hand-laid paper left over from Natural History of Raleigh covers. I folded and trimmed about a hundred little books and started printing the draft of images from my stock of rubber stamps and blocks.

The idea map emerged from thinking about these pictures of untold parables. As always, chance, opportunity and random influences guided me.

The closing image is from Andrew Lane, a zine artist whose work I first encountered through the 2020 Asheville Zine Fest exchange. I picked up his sticker at the Boone Bound book arts festival and put it right in front of my work station. So sad that Reagan, Newt Gingrich, and the bubbling forces of social media have brought truth into such peril.

The outer wrapper was designed to suspend the book in the envelope, to help that object make it through as a piece of first-class mail, which is much more tightly restricted than in the past. The Dinnerstein quote bookmark, re-printed on the fly for this project, has a one word omission error. It is such a fantastic quote.

Happy Trails, whatever Nov 5 brings.

Light at the Seam – a poem by Joseph Bathanti

The latest publication by The Paper Plant press is this broadside of a poem by Joseph Bathanti, a former NC Poet Laureate, ASU professor of creative writing, and the author of numerous volumes of poetry. This broadside was published in conjunction with ReVIEWING 14, the Black Mountain College conference which I attend each year and for which I create handouts related to the conference. This broadside is available for $10 plus $2 shipping – you can order here.

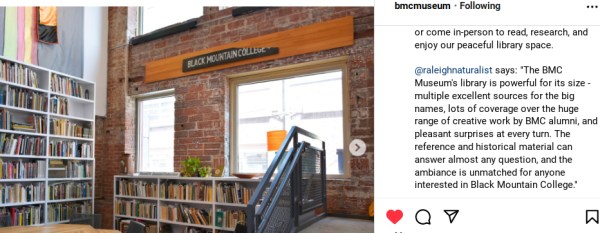

The Black Mountain College Museum + Art Center in Asheville has become ever more dear to my heart as I have developed a retirement habit of spending time most weeks in its library as well as that of the Center for Craft and the special collections room of Pack Library. The BMCM+AC staff used a quote from me to promote the library:

Soon after the BMC museum moved to its new larger location o Pack Square, I was privileged to conduct a special workshop in the library space celebrating the value of book arts in protecting freedom of cultural expression. Participants made paper, letterpress printed a quote on it, and explored my teaching collection of books as creative objects.

My longtime fascination with Black Mountain College has been rewarded with all the ways I have been able to benefit from attending the conference, visiting the museum, and teaching and learning in association with the wonderful community I have found through my pursuits. The current show, Weaving at Black Mountain College, was co-curated by Julie Thomson, a private scholar and friend who asked me to letterpressprint a sign and some response sheets for an interactive installation in the show.

The awful flip phone picture (by me) shows the letterpress sign and also a circular paper construction that I made emulating Buckminster Fuller’s Great Circles. Alice, program director at the museum, kindly allows my labeled paper construction to reside on this library tabletop. So here is my work in the art library I love to spend time in! Hope you visit this place sometime!

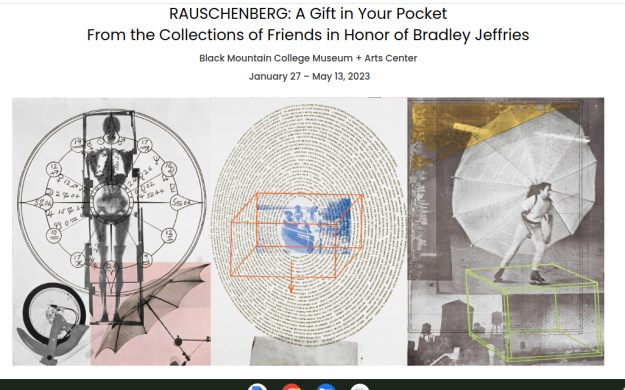

Highly Personal Rauschenberg Exhibit Brings Back Memories

all images shown in deference to Robert Rauschenberg’s estate

The Black Mountain College Museum + Art Center is hosting a traveling exhibit of a special set of work by Robert Rauschenberg – gifts, many made just for her, to his studio manager and confidant of 30 years, Bradley Jeffries. It’s an outstanding show with an initial grouping that is one of the most sensually beautiful I have ever seen in this or any museum. A good range of different media from this most versatile artist is shown, but a predominant one is solvent transfer, which captures pre-existing images, from text to photos to anything, in a dreamy and bluish hued tone of nostalgia.

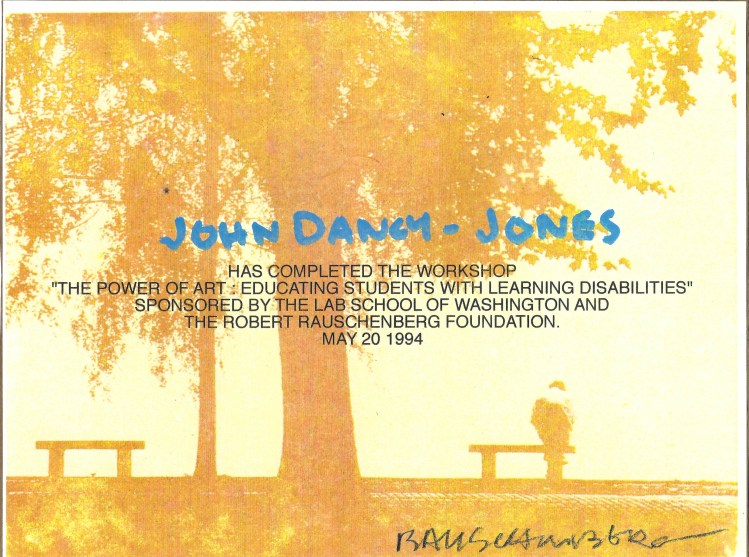

Much nostalgia for me in seeing a certificate of participation in a glass case, earned by Ms. Jeffries, for completion of the workshop The Power of Art, a program sponsored by Robert Rauschenberg at the Lab School, a self-contained day school in Georgetown in Washington, D.C. which serves students with learning differences. Her’s was for 1999; I was a charter participant the first year in 1994. I was a new art teacher at The Achievement School (now The Fletcher Academy) and applied for the workshop using student linoleum prints executed on scrap linoleum from the school’s gymnasium.

Mr Rauschenberg spent the day with us,as I describe on my Black Mountain College page.

Robert Rauschenberg found out as an adult that he had a learning disability ( as distinguished from being what he thought was “stupid”) from Sally Smith, founder of The Lab School. He became a supporter of the school, and the “Power of Art” program, of which I was a charter participant, rewarded art teachers who worked with that that population. Mr Rauschenberg treated us to a presentation along with his assistant, gave us signed posters, a five hundred dollar gift certificate to Jerry’s Artarama,and sat and listened to each of us present about our work. That evening, we were feted at a private reception at the National Gallery’s East Wing, and Mr Rauschenberg favored us with a tour of his own work on the walls. He discussed his decision to create the “white painting” while at Black Mountain (Josef Albers thought it a needless extreme), and he gave a vivid description of painting the huge 25 foot work which was on display in the main room -smearing his hands with the white lead paint for hours and then having to go into immediate treatment for weeks because of the lead poisoning. He was charming and down-to-earth, yet fragile and a bit ethereal in his personal presence. That was a wonderful day.

Below is a photcopy of my certificate. Sadly (and thoughtlessly) I displayed the original near a south-facing window and it has faded considerably. Just as bad, I used dorm room sticky to mount the poster Mr. Rauschenberg SIGNED. Such is life when you are a generalist with too many pies cooking. But now I have added this event to the several that have linked me repeatedly to Black Mountain College over the years, leading me now to be a private scholar in the field and an active participant in the activities of the wonderful BMC museum in downtown Asheville.