All Souls On Deck – Mail Art

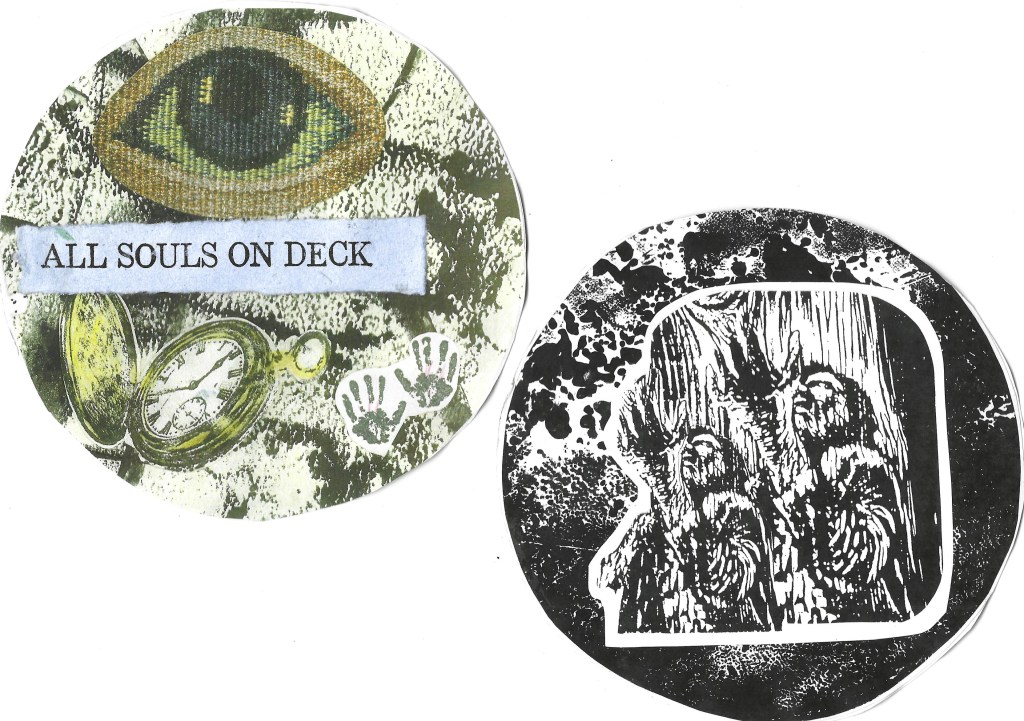

Here is JDJ letterpress printing a small title strip for the new project – but not in the letterpress shop -in my happy place, my library, which has been engulfed for weeks in a massive effort – 2600 cut-outs, 1400 gluings, and a whole lot of folding and wrangling to construct a set of round tarot-type art cards that are a care package for our times.

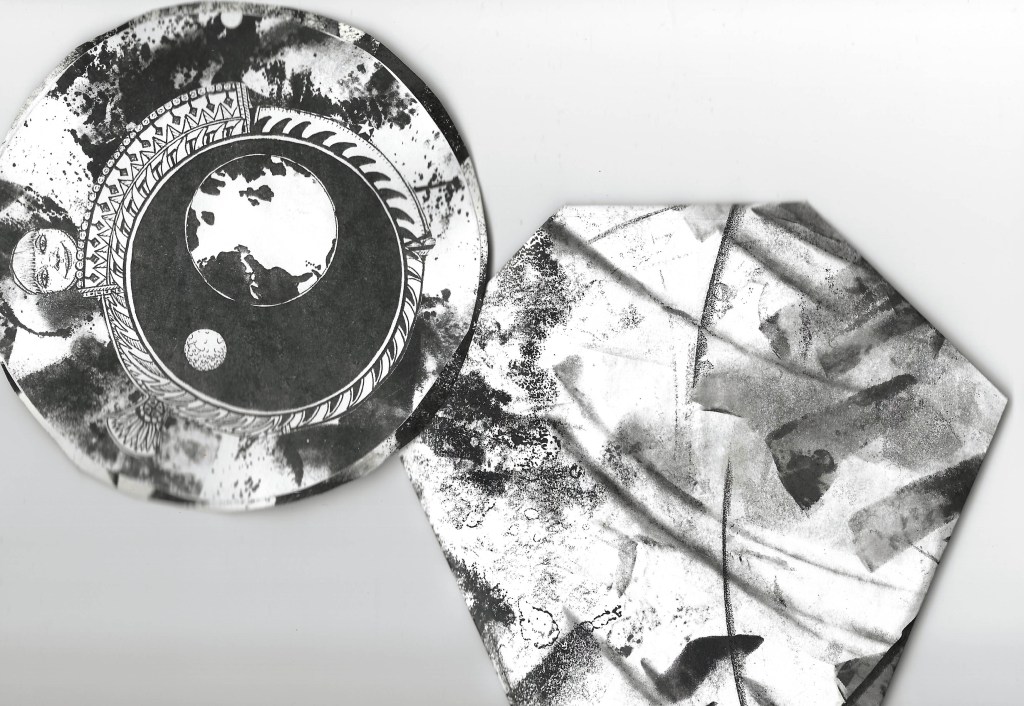

The set comes wrapped in a “decorative” origami envelope – this is the last big use of this black and white letterpress clean-up material for a long while – I promise!

Many thanks to the artists whose work was appropriated: David Larson, Jen Coon, Leslie Pruneau, Matt Cooper, Lily Dancy-Jones and John Justice. Gratitude to and inspiration from Sebastian Matthews and Jonathan Laurer, who recently sent me beautiful card sets.

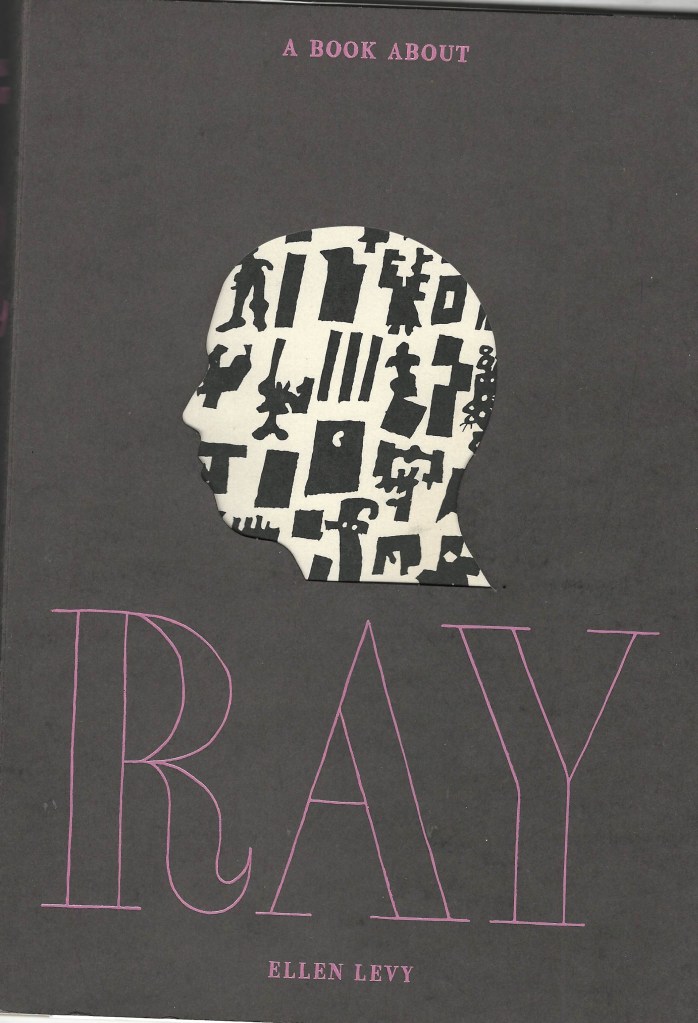

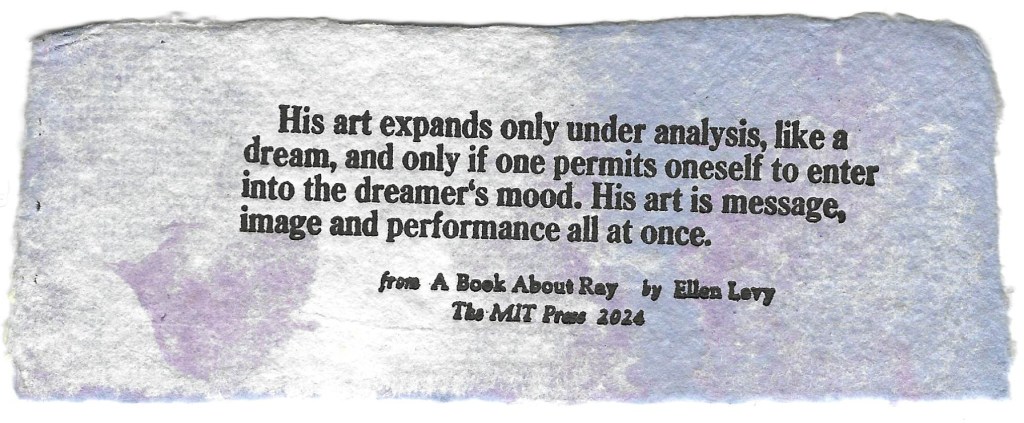

A Book About Ray by Ellen Levy

A Book About Ray by Ellen Levy

Looking with side-curve head curious what comes next

Both in and out of the game and watching and wondering at it.

From “Me Myself”

Walt Whitman

I knew I wanted to be a writer by age 15, but I didn’t come to art as a practice until experiencing the large exhibit of Ray Johnson’s correspondence art in my hometown of Raleigh in 1976. The stunning sense of wonder and delight in the everyday and the radicalization of the locus and purpose of art in this show set me on the life-long journey I have traveled through book arts, performance art, alternative small press publishing and mail art. Yet Ray Johnson and my experience in corresponding with him over the following year were and have remained an enigma to me, even as I have studied his life and career over the last decade due to Sebastian Matthew’s show and other events at the Black Mountain College Museum & Art Center. Ellen Levy’s new book offers the best understanding of Ray and his work I have ever encountered, and her eminently readable and remarkably thorough account is a gift to anyone who is a fan of Ray’s work.

Ray Johnson was born in 1927, just a year after my father, in Detroit Michigan, showed talent early, attended Black Mountain College, moved to New York City with one of his teachers, and became known, eventually quite notoriously, as “New York’s most famous unknown artist,” That irony is a perfect signpost for the absolutely unique, frequently puzzling, and always intriguing art of Ray Johnson, which Ellen Levy shows to be unified in all its many formats as a body of very important work with a strong consistent aesthetic. His life seemed to have been completely devoured by his art, but he lived art so beautifully and honestly that one can always learn something from him and usually get a big laugh or chuckle as well.

Levy gives us not a biography, but the story of his art, which frames his life but excludes what the art doesn’t present for examination. For years I have followed the work of friends who have emphasized the collage work, the way Ray fits into the canon of major art, and the unique pathways he found in correspondence and performance art. (Sebastian Matthews, Kate Dempsey Martineau, and Julie Thomson respectively). Ellen Levy clearly immersed herself with radical depth into the vast and difficult array of Ray Johnson’s work and practices and brings all of the above into a coherent focus. Her approach is described on the dust jacket as “elliptical” and she is certainly remarkably thorough as she sifts through Ray’s archival history, one he planned and organized for just such a researcher as herself. Ray himself comes across through the story as unchanging and un-changable, but she finds the plot in his endlessly various narratives and makes us feel the arc and inevitable denouement of his story, which he ultimately fused with his personal life in a tragic way. But that doomed arc touched on large and important accomplishments and this book admirably argues for their place in the legacy of the New York School of artists and its outgrowths.

I love the ways in which Ray Johnson was famous-adjacent, and I learned from Levy’s book just how obsessed he was with fame and its ecology of connections. The quote about “most famous unknown” is from a New York Times art critic mentioning one of his relatively few gallery shows. The Village Voice, in its very first issue in 1955, ran a story about Ray and his moticos, which was the series that seemed to take him away from painting and into what became correspondence art. Levy documents Ray’s substantial exhibition in a couple of major galleries and many less so, but he strongly resisted exhibition and subverted any attempts to control his process. Subversion became central to his work, especially in regard to fame. Like many, my favorite Ray Johnson collages are the Elvis and James Dean portraits, which are so painterly as not to qualify for Levy as proper “moticos.” By the time period in which I corresponded with Ray, Levy describes him as losing his way a bit, partly due to the overwhelming but not particularly gratifying demands of mass correspondence. Ellen Levy discovered him well after the turn of the century through the semi-viral video “How to Draw a Bunny,” which lovingly and convincingly argues that Ray’s suicide in 1995 was a genuine act of performance art. This book certainly makes one feel Ray might have finally felt that his work had indeed eclipsed his life.

Ray was a performance artist in direct and diffused ways. His contributions to the Happenings movement in postmodern art included announced gallery events as well as improvised NY sidewalk encounters while foraging for collage supplies. His sidewalk display of moticos, with the assistance of friend and art critic Suzi Gablick, could be compared to Joseph Beuys. But whenever Ray Johnson was in public and also in many, if not most, personal situations, he was acting out a persona recognizable to anyone who got to know him. When mystifying or annoying audiences on his college art lecture tour, offering impossible trade terms and conditions to a gallery owner, being interviewed – oh, the interviews! A great companion to Levy’s book is That Was the Answer, edited by Julie Thomson, which chronicles the hilarious, telling and charming way Ray resisted any normal interview. Yet he always seems, well, deadly serious. The empty silhouette of Ray on the cover of A Book About Ray seems a fitting portrait of a person who let his work and artistic beliefs fill out all the corners of his life.

Ray Johnson is difficult, in many ways. Ellen Levy says “I like difficult art.” With his monotone sarcasm and endless detours into esoteric or oblique references added to his grave mistrust of the commercial aspect of fine art, Ray never made it truly big in Fine Art, but his cult-like following and the gradually building body of scholarship and retrospect exhibitions offer anyone willing to make the effort a chance to discover the wonders and delights of this artist. His whimsical use of everyday images, verbal coincidences, and found puns provided a vocabulary he used to describe a popular culture with which he seemed both obsessed and slightly appalled. This book is a fine handbook for your arduous journey.

This is the bookmark I will be giving away at the upcoming conference

ReVIEWING Black Mountain College

Co-hosted by BMCM+AC and UNC Asheville

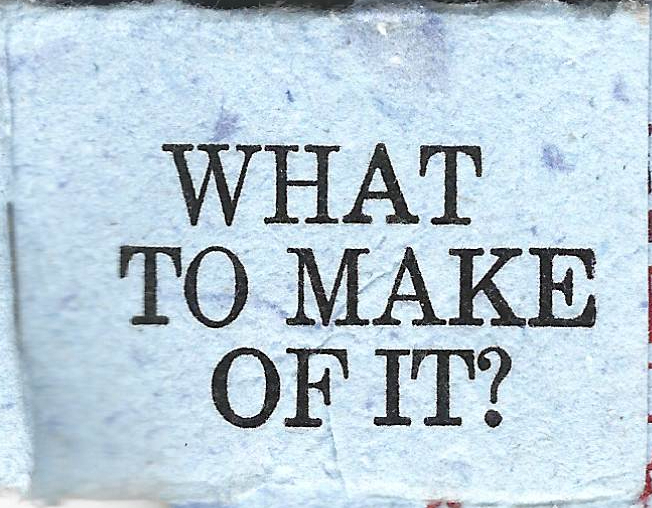

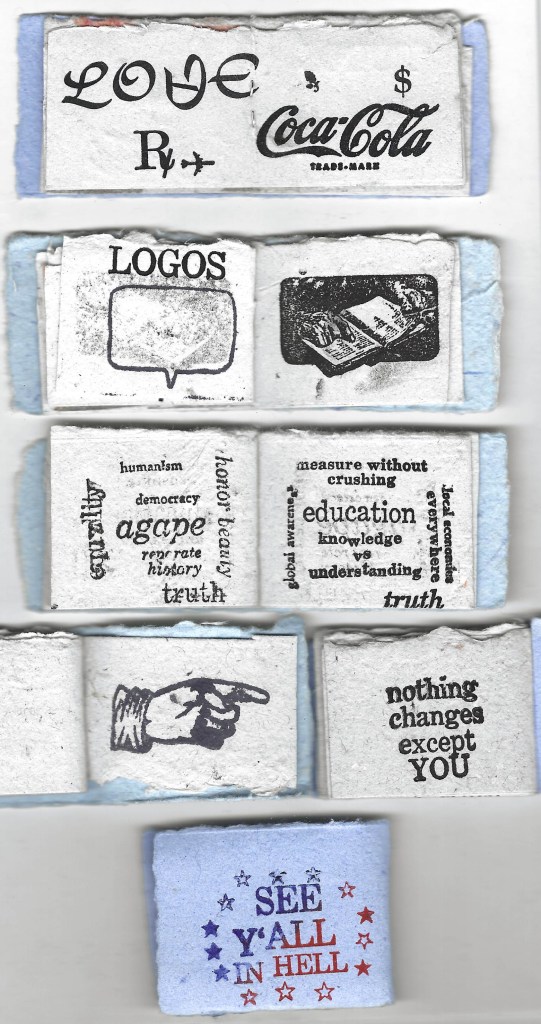

What To Make of It? What will YOU make out of it: mail art

Helene’s fury found me two-thirds through a major mail art project. With the content committed to a pre-election release, I found a way to keep working on it, printing by battery light with a helpful mirror just outside the studio on sunny days. This piece was always going to be “rustic,” even for me, but it was finished in near desperation, taking breaks from printing to shovel silt out of the book arts barn.

The inspiration for this piece came from Leslie Pruneau, a talented and well-established Raleigh artist, who sent me a wonderful tiny book as a gift in return for my mail art. As soon as I saw it, I knew how I wanted to use the hundreds of one inch strips of hand-laid paper left over from Natural History of Raleigh covers. I folded and trimmed about a hundred little books and started printing the draft of images from my stock of rubber stamps and blocks.

The idea map emerged from thinking about these pictures of untold parables. As always, chance, opportunity and random influences guided me.

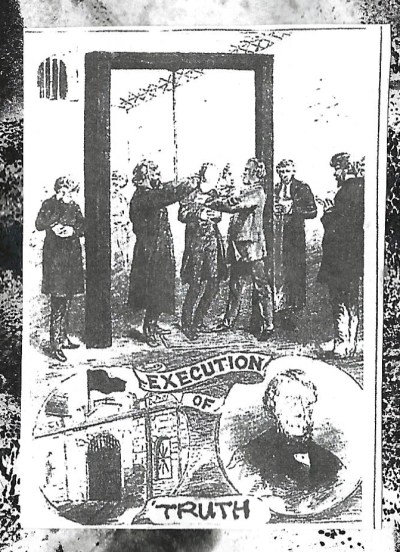

The closing image is from Andrew Lane, a zine artist whose work I first encountered through the 2020 Asheville Zine Fest exchange. I picked up his sticker at the Boone Bound book arts festival and put it right in front of my work station. So sad that Reagan, Newt Gingrich, and the bubbling forces of social media have brought truth into such peril.

The outer wrapper was designed to suspend the book in the envelope, to help that object make it through as a piece of first-class mail, which is much more tightly restricted than in the past. The Dinnerstein quote bookmark, re-printed on the fly for this project, has a one word omission error. It is such a fantastic quote.

Happy Trails, whatever Nov 5 brings.

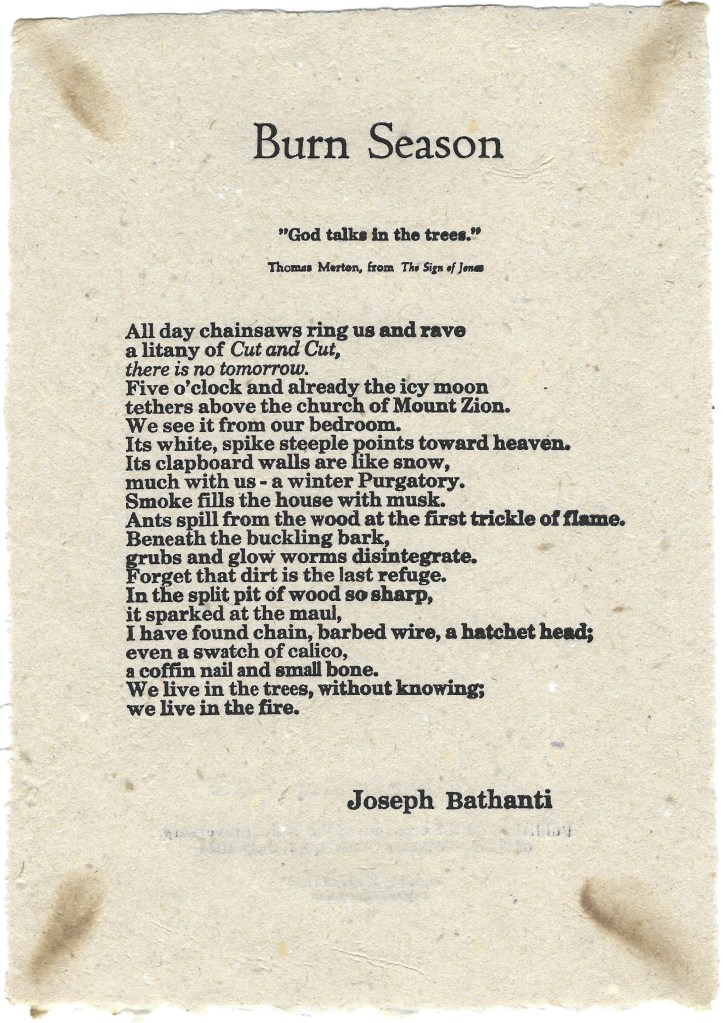

Burn Season Broadside Was an Honor to Produce

The latest publication from The Paper Plant is this broadside featuring a wonderful poem by Joseph Bathanti, who is being honored at the North Carolina Writers Conference on July 20, 2024 in Black Mountain.

A commissioned piece; not available from The Paper Plant.

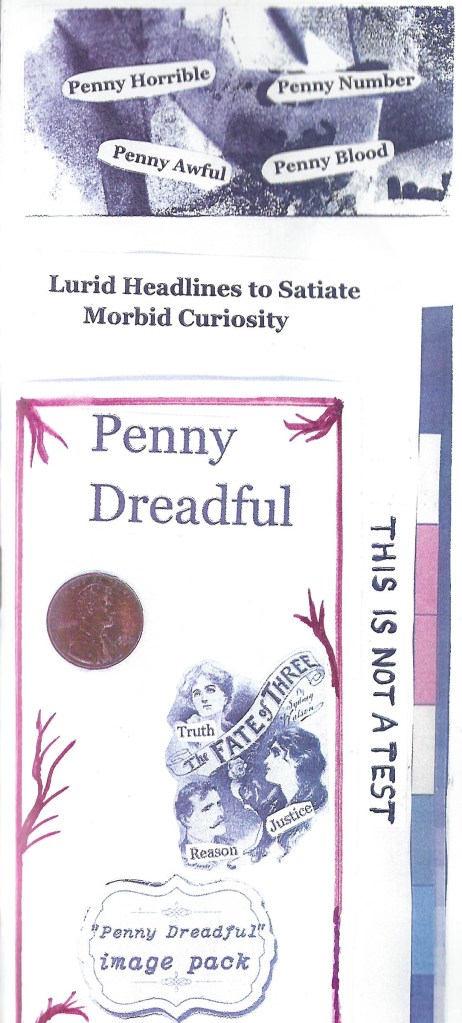

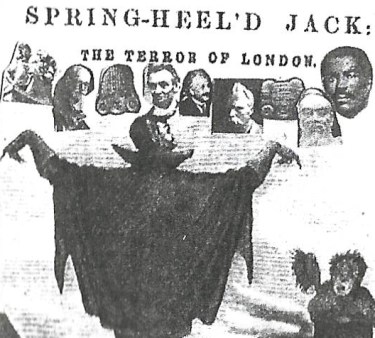

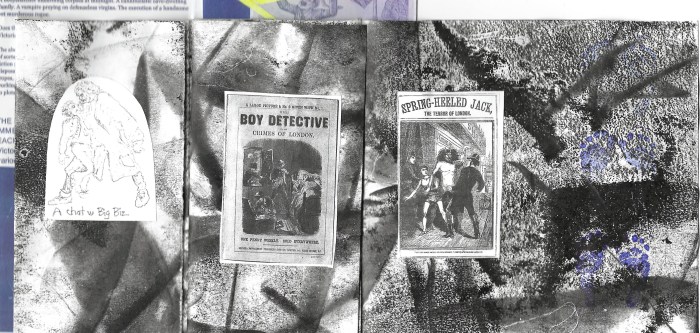

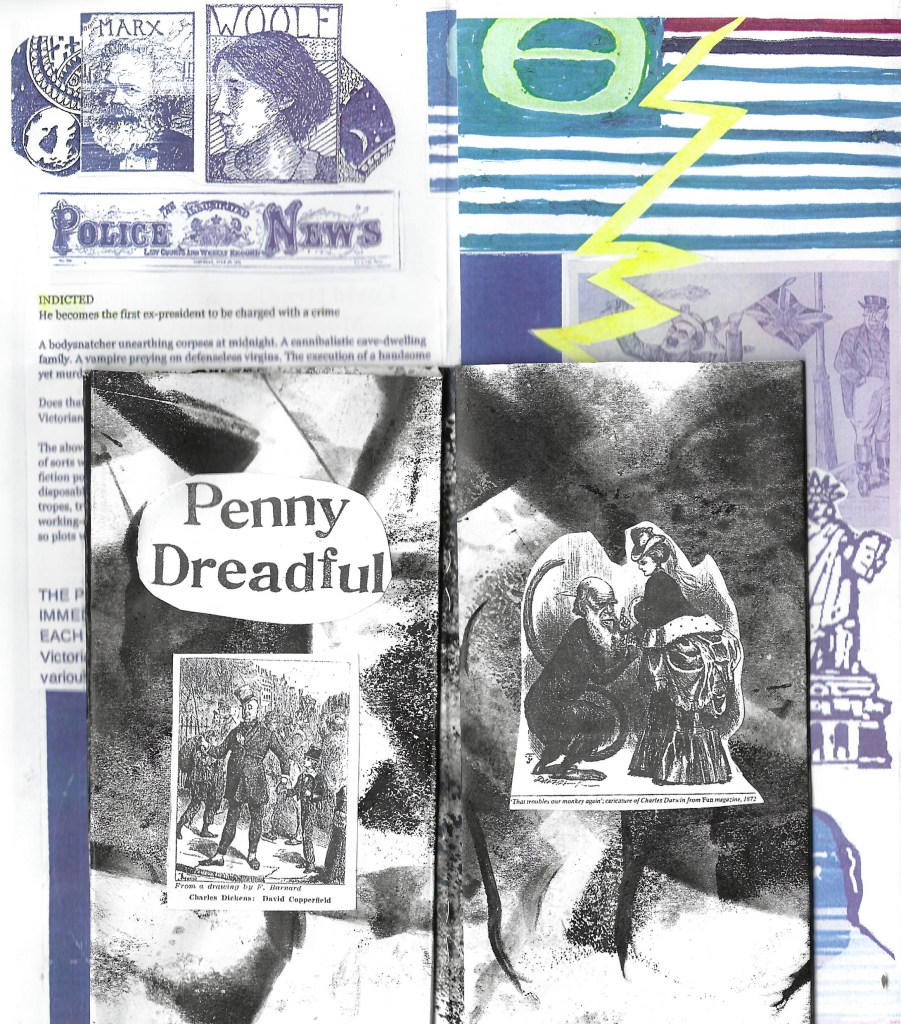

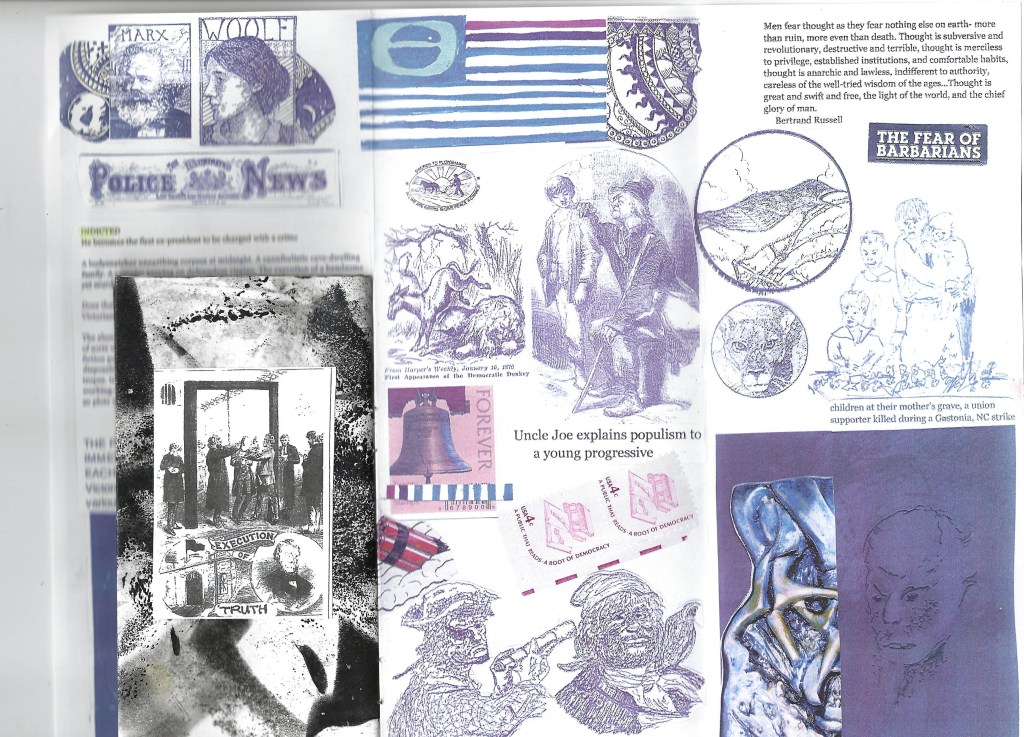

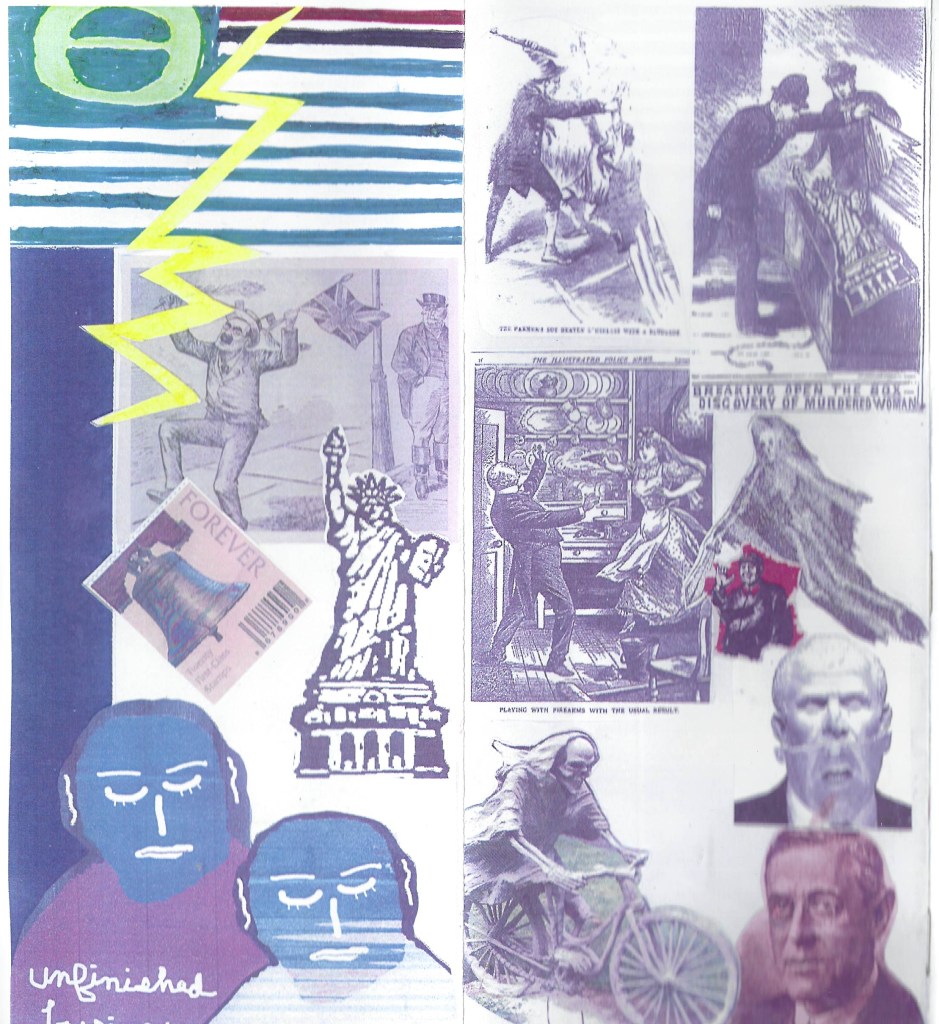

PENNY DREADFUL an essay in small print

My latest and biggest ever mail art is out in the world in an edition of 120! Based on an early form of street literature I learned about from Dr. Charles Edge at UNC-CH in the early 70’s. I previously used the format in a self-publishing project with 6th graders at Glenwood Elementary my final year in Chapel Hill. Sent one year from an inauguration that will be a watershed for our country – one way or the other.

The format is a 2-sided color photocopy enclosing a small booklet made of an 11×17 sheet strategically used to clean off excess ink from the platen after letterpress printing nature book covers. I also used these for the zine version of my pandemic mail art piece, Plague Daze.

Historic images of Penny Dreadful covers and other historical print images (occasionally modified) were cut out and glued into the booklet. Over 3000 pieces! Not all are shown.

Throughout, the reproduced pencil drawings are my tracings and re-drawings of print images. Hilariously, the mounted penny is the specific reason this mailing is slightly too thick to qualify as first class by current (much stricter) regulations. Also, mounting the penny with glue on the back side is surely a defacement, which is a federal offense. I love the subversion but I fervently hope none get returned (109 are in the mails as I write).

A big thanks to contributors of images: David Larson, John Justice, Jonathan Laurer and of course the online resources for Penny Dreadfuls. This mailing was sent in the memory of Ray Johnson, correspondance artist extraordinaire. Richard C, Ray J’s curator, and John Justice received draft versions of the project which were essential in finalizing the final design. Mail art lives!

Our country and its democracy, such as it is, WILL survive – American history is filled with far worse episodes. Besides, the really big boys are not going to let our lucrative systems break down – and The System is inexorably getting more progressive and global all the time – but this has been a hell of a wake-up call for all of us. God bless us all.

Feedback on Penny Dreadful

Mary R: Shadow and light conjoined in a delightful dreadful death of democracy, a fine memento mori for Ray….. most grateful and amazed!

Alyssa S: It was such s surprise and delight to receive! I’m looking forward to spending more time with it. Each look, I catch something I didn’t see before.

Cheryl C T: There’s so much to see. Each time I look, I find another interesting detail.

Lee M C: I am really moved by this work..opening it and being..yes this is today and yesterday and the impending proverbial bad penny! amazing imagery , prophetic synchronicity

Eric N:Got my Penny Dreadful mail art a few days ago. Thank you so much–a remarkable assemblage. I love it

Marcia C: What a wonderful surprise to have your very cool little book arrive in the mail. Thank you so much! Penny Dreadful is a rouge book that has some wonderful fingerprints on it. I can see all your hand work and paste and stick and fold.

Jen C.: You have lit up my imagination once again, John.